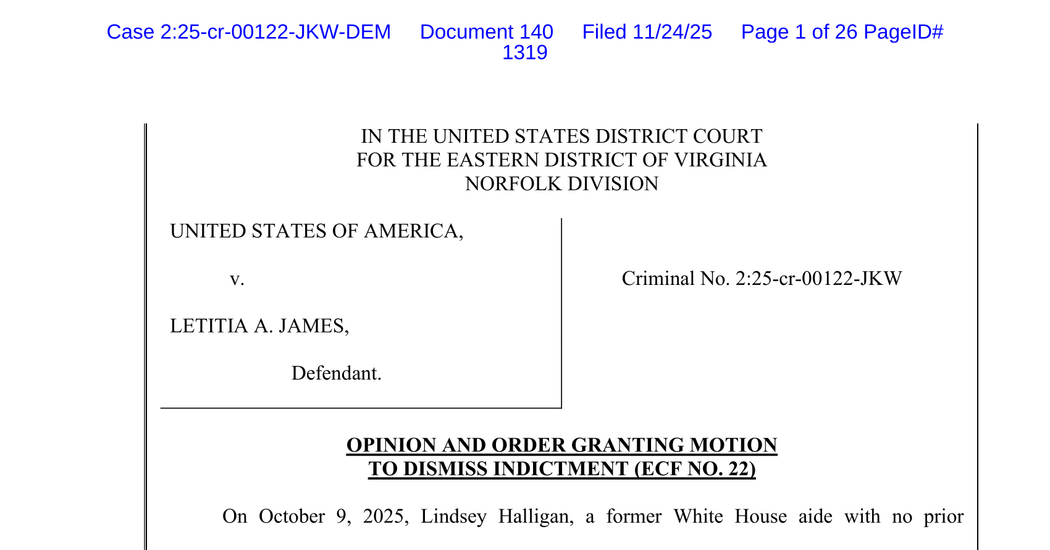

Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 1319 Page 1 of 26 PageID# IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA NORFOLK DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, V. LETITIA A. JAMES, Defendant. Criminal No. 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW OPINION AND ORDER GRANTING MOTION TO DISMISS INDICTMENT (ECF NO. 22) On October 9, 2025, Lindsey Halligan, a former White House aide with no prior prosecutorial experience, appeared before a federal grand jury in the Eastern District of Virginia. Having been appointed Interim U. S. Attorney by the Attorney General just two weeks before, Ms. Halligan secured a two-count indictment charging New York Attorney General Letitia James with bank fraud and making false statements to a financial institution. Ms. James now moves to dismiss the indictment on the ground that Ms. Halligan, the sole prosecutor who presented the case to the grand jury, was unlawfully appointed in violation of 28 U. S. C. § 546 and the Constitution’s Appointments Clause. As explained below, I agree with Ms. James that the Attorney General’s attempt to install Ms. Halligan as Interim U. S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia was invalid. And because Ms. Halligan had no lawful authority to present the indictment, I will grant Ms. James’s motion and dismiss the indictment without prejudice. Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 1320 Page 2 of 26 PageID# I. BACKGROUND A. Legal Background “The Appointments Clause prescribes the exclusive means of appointing ‘Officers [of the United States].” Lucia v. SEC, 585 U. S. 237, 244 (2018). The text of the Clause contemplates two types of officers: “principal” and “inferior” officers. See Morrison v. Olson, 487 U. S. 654, 670-71 (1988). Principal officers must be appointed by the President “with the Advice and Consent of the Senate.” U. S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 2. The same process “is also the default manner of appointment for inferior officers.” Edmond v. United States, 520 U. S. 651, 660 (1997). But the Framers “recognized that requiring all officers of the Federal Government to run the gauntlet of Presidential nomination and Senate confirmation would prove administratively unworkable.” Kennedy v. Braidwood Mgmt., Inc., 606 U. S. 748, 760 (2025) (emphasis in original). “So on one of the last days of the Constitutional Convention[,] . they authorized an additional and streamlined method of appointment for inferior officers” in the final provision of the Appointments Clause. Id. That provision, “sometimes referred to as the ‘Excepting Clause,”” Edmond, 520 U. S. at 660, permits Congress to “by Law vest” the appointment of inferior officers “in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.” U. S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 2. “For United States Attorneys, Congress has preserved the constitutional default rule of Presidential appointment and Senate confirmation.”¹ United States v. Giraud, F. Supp. 3d No. 1: 24-CR-768, 2025 WL 2416737, at *6 (D. N. J. Aug. 21, 2025) (Giraud II), appeal filed, No. 25-2635 (3d Cir. Aug. 25, 2025); see 28 U. S. C. § 541(a) (“The President shall appoint, by and at 5. 1 The parties agree that U. S. Attorneys are inferior officers. ECF No. 22 at 9; ECF No. 43 2 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 3 of 26 PageID# 1321 with the advice and consent of the Senate, a United States attorney for each judicial district.”). Congress has also established a mechanism, set forth in 28 U. S. C. § 546, for appointing interim U. S. Attorneys when a vacancy arises. ² Section 546 essentially “divide[s] the responsibility for making interim appointments between the Attorney General and the district courts.” United States v. Baldwin, 541 F. Supp. 2d 1184, 1192 (D. N. M. 2008). It provides in full: (a) Except as provided in subsection (b), the Attorney General may appoint a United States attorney for the district in which the office of United States attorney is vacant. (b) The Attorney General shall not appoint as United States attorney a person to whose appointment by the President to that office the Senate refused to give advice and consent. (c) A person appointed as United States attorney under this section may serve until the earlier of- (1) the qualification of a United States attorney for such district appointed by the President under section 541 of this title; or (2) the expiration of 120 days after appointment by the Attorney General under this section. (d) If an appointment expires under subsection (c)(2), the district court for such district may appoint a United States attorney to serve until the vacancy is filled. The order of appointment by the court shall be filed with the clerk of the court. 28 U. S. C. § 546. B. Factual Background On January 20, 2025, Jessica Aber, who had been nominated by President Biden and confirmed by the Senate, resigned from her position as U. S. Attorney for the Eastern District of 2 Another statute, the Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998 (“FVRA”), 5 U. S. C. §§ 3345- 3349d, allows the President to “direct certain officials to temporarily carry out the duties of a vacant [office requiring Presidential appointment and Senate confirmation] in an acting capacity.” NLRB v. SW Gen., Inc., 580 U. S. 288, 293 (2017). The FVRA is not at issue in this case. 3 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 4 of 26 PageID# 1322 3 Virginia. The following day, the Attorney General appointed Erik Siebert as Interim U. S. Attorney under 28 U. S. C. § 546. 4 Mr. Siebert’s 120-day interim appointment was set to expire on May 21, 2025. So, on May 9, 2025, the judges of the district exercised their authority under section 546(d) to appoint Mr. Siebert to continue in his role, effective May 21. 5 On September 19, 2025, Mr. Siebert informed colleagues of his resignation. According to news reports, Mr. James and former FBI Director James Comey. Mr. Siebert’s resignation came hours after President Trump told reporters at the White House he “want[ed] [Mr. Siebert] out.”8 3 Press Release, United States Attorney’s Office, Eastern District of Virginia, U. S. Attorney Jessica D. Aber Announces Resignation (Jan. 17, 2025), attorney-jessica-d-aber-announces-resignation. 4 Press Release, United States Attorney’s Office, Eastern District of Virginia, Erik Siebert Appointed Interim U. S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia (Jan. 21, 2025), virginia. 5 United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Appointment of Erik S. Siebert as Interim U. S. Attorney Effective May 21, 2025 (May 9, 2025), may-21-2025. from 6 Glenn Thrush et al., U. S. Attorney Investigating Two Trump Foes Departs Amid Pressure President, (Sept. 2025), N. Y. Times 19, 7 Id.; Salvador Rizzo, Perry Stein & Jeremy Roebuck, Top Virginia Prosecutor Resigns Amid Criticism over Letitia James Investigation, Wash. Post (Sept. 20, 2025), virginia/; The Associated Press, U. S. Attorney Resigns Under Pressure From Trump to Charge N. Y. AG Letitia James, NPR (Sept. 20, 2025), attorney-virginia-resigns-letitia-james-probe. 8 Thrush et al., supra note 6. 4 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 5 of 26 PageID# 1323 media: The next day, President Trump posted (and later deleted) the following message on social Pam: I have reviewed over 30 statements and posts saying that, essentially, “same old story as last time, all talk, no action. Nothing is being done. What about Comey, Adam “Shifty” Schiff, Leticia??? They’re all guilty as hell, but nothing is going to be done.” Then we almost put in a Democrat supported U. S. Attorney, in Virginia, with a really bad Republican past. A Woke RINO, who was never going to do his job. That’s why two of the worst Dem Senators PUSHED him so hard. He even lied to the media and said he quit, and that we had no case. No, I fired him, and there is a GREAT CASE, and many lawyers, and legal pundits, say so. Lindsey Halligan is a really good lawyer, and likes you, a lot. We can’t delay any longer, it’s killing our reputation and credibility. They impeached me twice, and indicted me (5 times!), OVER NOTHING. JUSTICE MUST BE SERVED, NOW!!! President DJT⁹ Less than 48 hours after President Trump’s post, on September 22, 2025, the Attorney General issued an order “authorizing Lindsey Halligan to be the Interim United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia during the vacancy in that office” (“September 22 Order”). Att’y Gen. Order No. 6402-2025. The September 22 Order cites only 28 U. S. C. § 546 as the basis for Ms. Halligan’s appointment. Id. On October 9, 2025, a grand jury sitting in the Eastern District of Virginia returned a two- count indictment against Ms. James, charging her with bank fraud, in violation of 18 U. S. C. § 1344, and making false statements to a financial institution, in violation of 18 U. S. C. § 1014. ECF No. 1. The charges stem from allegations that Ms. James falsely claimed that she would use a Norfolk, Virginia home as a secondary residence to secure a more favorable mortgage rate. Ms. 9 Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump), Truth Social (Sept. 20, 2025, at 18: 44 ET), 5 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 6 of 26 PageID# 1324 Halligan was the only prosecutor who participated in the Government’s presentation to the grand jury, and only her signature appears on Ms. James’s indictment. Id. at 5. 10 C. Procedural History On October 24, 2025, Ms. James moved to dismiss the indictment on the ground that Ms. Halligan’s appointment was unlawful under section 546 and violated the Appointments Clause. ECF No. 22. Later that day, the Honorable Jamar K. Walker transferred Ms. James’s motion to me pursuant to an October 21 order issued by the Honorable Albert Diaz, Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. ECF No. 23. Chief Judge Diaz had designated and assigned me to “sit in the Eastern District of Virginia for the limited purpose of hearing and determining . motions concerning the appointment, qualification, or disqualification of” Ms. Halligan or the U. S. Attorney’s Office. ECF No. 23-1 at 1. Finding it “necessary to determine the extent of [Ms. Halligan’s] involvement in the grand jury proceedings,” I ordered the Government on October 28 to submit for in camera review “all documents relating to [Ms. Halligan’s] participation” before the grand jury, “along with complete grand jury transcripts.” ECF No. 28. On October 31, I received a partial transcript containing only Ms. Halligan’s presentation of evidence and witness testimony. Subsequently, on November 6, the Government provided a complete transcript of the proceeding, which included Ms. Halligan’s opening and closing remarks. ECF No. 48. On November 3, the Government responded in opposition to Ms. James’s motion. ECF No. 43. Also that day, the Government filed an order from the Attorney General dated October 10 Citations to page numbers are to those generated by CM/ECF. 6 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 7 of 26 PageID# 1325 31, 2025 (“October 31 Order”). Att’y Gen. Order No. 6485-2025. The October 31 Order reads in its entirety: Id. On September 22, 2025, I exercised the authority vested in the Attorney General by 28 U. S. C. § 546 to designate and appoint Lindsey Halligan as the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia. See Att’y Gen. Order No. 6402-2025. For the avoidance of doubt as to the validity of that appointment, and by virtue of the authority vested in the Attorney General by law, including 28 U. S. C. §[§] 509, 510, and 515, I hereby appoint Ms. Halligan to the additional position of Special Attorney, as of September 22, 2025, and thereby ratify her employment as an attorney of the Department of Justice from that date going forward. As Special Attorney, Ms. Halligan has authority to conduct, in the Eastern District of Virginia, any kind of legal proceeding, civil or criminal, including grand jury proceedings and proceedings before United States Magistrates and Judges. In the alternative, should a court conclude that Ms. Halligan’s authority as Special Attorney is limited to particular matters, I hereby delegate to Ms. Halligan authority as Special Attorney to conduct and supervise the prosecutions in United States v. Comey (Case No. 1: 25-CR-00272) and United States v. James (Case No. 2: 25-CR-00122). In addition, based on my review of the grand jury proceedings in United States v. Comey and United States v. James, I hereby exercise the authority vested in the Attorney General by law, including 28 U. S. C. §[§] 509, 510, and 518(b), to ratify Ms. Halligan’s actions before the grand jury and her signature on the indictments returned by the grand jury in each case. Ms. James filed her reply on November 10. 11 ECF No. 56. On November 13, I heard oral argument from the parties and took the matter under advisement. ECF No. 69. During the hearing, I raised concerns about the Attorney General’s ability to review Ms. Halligan’s presentation to the grand jury in United States v. Comey when, as of October 31, the Government had not yet received the complete transcript of the proceeding. ECF No. 89 at 36-37. My questioning prompted the Government to file a new ratification order from the Attorney General in this case on November 11 In addition to the parties’ briefs, I have also considered an amicus brief from a bipartisan group of former federal judges and U. S. Attorneys. ECF No. 55. 7 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 8 of 26 PageID# 1326 17. In that order, the Attorney General stated she had “reviewed the entirety of the record now available to the government” and again “ratif[ied] Ms. Halligan’s actions before the grand jury and her signature on the indictment returned.” Att’y Gen. Order No. 6495-2025. II. DISCUSSION Resolving Ms. James’s motion requires me first to decide whether Ms. Halligan was validly appointed as Interim U. S. Attorney under section 546 and the Appointments Clause. If the answer to that question is yes, I need not go any further, and Ms. James’s motion must be denied. But if the answer is no, and Ms. Halligan had no authority to present Ms. James’s indictment to the grand jury, then the question becomes, what remedy is appropriate? Should the indictment be dismissed? And if so, should the dismissal be with or without prejudice? I address these issues in turn, beginning with whether Ms. Halligan’s appointment was valid under section 546. A. Ms. Halligan’s appointment violated section 546. According to the Government, this case is “simple.” ECF No. 43 at 8. In its view, the “one and only” limitation on the Attorney General’s authority to appoint interim U. S. Attorneys under section 546 is subsection (b), which bars the Attorney General from appointing anyone whom the Senate has refused to confirm. Id. at 3, 8, 15. “Nothing in the text,” it continues, “explicitly or implicitly” precludes the Attorney General from making multiple interim appointments during a vacancy. Id. at 8. Thus, it concludes, because “the Senate has not refused advice and consent to Ms. Halligan,” the Attorney General “lawfully appointed [her] as interim U. S. Attorney” on September 22. Id. at 8. Ms. James counters that section 546 “vest[s]” the Attorney General “with 120 total days to appoint an interim U. S. Attorney”; after that period, “the exclusive authority to appoint an interim U. S. Attorney belongs to the district court.” ECF No. 22 at 11. Therefore, she argues, Ms. 8 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 9 of 26 PageID# 1327 Halligan’s appointment was unlawful because the Attorney General’s appointment authority expired on May 21 with the end of Mr. Siebert’s 120-day term. Id. Ms. James has the better reading of the statute. “The preeminent canon of statutory interpretation requires [courts] to ‘presume that [the] legislature says in a statute what it means and means in a statute what it says there. BedRoc Ltd., LLC v. United States, 541 U. S. 176, 183 (2004) (quoting Conn. Nat’l Bank v. Germain, 503 U. S. 249, 253-54 (1992)). “Thus, [my] inquiry begins with the statutory text, and ends there as well if the text is unambiguous.” Id. “The plainness or ambiguity of statutory language is determined by reference to the language itself, the specific context in which that language is used, and the broader context of the statute as a whole.” Robinson v. Shell Oil Co., 519 U. S. 337, 341 (1997). Section 546 is unambiguous. Subsection (a) begins by authorizing the Attorney General to “appoint a United States attorney for the district in which the office of United States attorney is vacant.” 28 U. S. C. § 546(a). Subsection (c)(2), however, imposes a time limit on appointments made by the Attorney General. It specifies that “[a] person appointed as United States attorney” under the statute “may serve until . the expiration of 120 days after appointment by the Attorney General.” Id. § 546(c)(2). Subsection (d) then provides a single option for how subsequent interim appointments may be made: “If an appointment expires under subsection (c)(2), the district court for such district” and only the district court “may appoint a United States attorney to serve until the vacancy is filled.” Id. § 546(d). The text and structure of subsection (d) in particular make clear the appointment power (1) shifts to the district court after the 120-day period and (2) does not revert to the Attorney General if a court-appointed U. S. Attorney leaves office before a Senate-confirmed U. S. Attorney is installed. The first word in subsection (d) “if” introduces a conditional clause that establishes 9 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 10 of 26 PageID# 1328 the condition triggering the district court’s authority. See The Chicago Manual of Style ¶ 5. 235 (18th ed. 2024) (“A conditional clause . is an adverbial clause, typically introduced by if or unless ., establishing the condition in a conditional sentence. Usually this is a direct condition, indicating that the main clause . is dependent on the condition being fulfilled.”). That condition is met once “an appointment expires under subsection (c)(2).” 28 U. S. C. § 546(d) (emphasis added). The indefinite article “an” points “to a nonspecific object, thing, or person that is not distinguished from other members of a class,” Bryan A. Garner, Garner’s Modern English Usage 1195 (5th ed. 2022), so the expiration of any single Attorney General appointment satisfies the condition. Thus, if, as here, a court-appointed U. S. Attorney resigns, the district court retains the authority to make another interim appointment because the triggering event the expiration of “an appointment” under subsection (c)(2) has already occurred. Finally, the conjunction “until” in subsection (d)’s main clause defines the duration of the district court’s authority. It lasts from the moment the condition is first met “up to the time that” the vacancy is filled by a Senate- confirmed appointee. Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary 1297 (10th ed. 1997). This reading is reinforced by the negative-implication canon, which recognizes that the “expression of one thing implies the exclusion of others.” Antonin Scalia & Bryan A. Garner, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts 107 (2012). To be sure, the Supreme Court has cautioned that the “force of any negative implication . depends on context,” Marx v. Gen. Revenue Corp., 568 U. S. 371, 381 (2013), and that the “canon applies only when circumstances support a sensible inference that the term left out must have been meant to be excluded,” NLRB v. SW Gen., Inc., 580 U. S. 288, 302 (2017) (internal quotation marks omitted). Here, however, “the inference is not just sensible but overwhelming.” Johnson v. White, 989 F. 3d 913, 918 (11th Cir. 2021). Congress assigned the authority to appoint interim U. S. Attorneys to different actors 10 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 11 of 26 PageID# 1329 in different parts of the same statute: first to the Attorney General in subsection (a), and then to the district court in subsection (d). The omission of the Attorney General in subsection (d), when combined with her inclusion in subsection (a), is strong evidence Congress did not intend for the Attorney General to retain appointment power beyond 120 days. Cf. United States v. Hilario, 218 F. 3d 19, 23 (1st Cir. 2000) (“The absence of any temporal limit [in subsection (d)] strikes us as deliberate, rather than serendipitous, especially in view of the contrast between adjacent sections of a single statute.”). Adopting the Government’s contrary reading would render subsection (d) “insignificant,” leaving it to “lie dormant in all but the most unlikely situations.” TRW Inc. v. Andrews, 534 U. S. 19, 31 (2001) (internal quotation marks omitted); see id. (“[A] statute ought, upon the whole, to be so construed that, if it can be prevented, no clause, sentence, or word shall be superfluous, void, or insignificant.” (internal quotation marks omitted)); Loughrin v. United States, 573 U. S. 351, 358 (2014) (“[C]ourts must give effect, if possible, to every clause and word of a statute.” (internal quotation marks omitted)). Under the Government’s interpretation, Attorney General appointees can “serve indefinitely” “without Senate confirmation” as long as the Attorney General “revisit[s] her interim appointments every 120 days.” ECF No. 43 at 9. But if that were correct, the Attorney General could prevent interim appointments from ever “expir[ing] under subsection (c)(2),” which in turn would prevent the district court from ever exercising its appointment power under subsection (d). 28 U. S. C. § 546(d). Such a result would run counter to the principle that courts must avoid interpreting statutes in a way that has the “practical effect” of rendering a provision “entirely superfluous in all but the most unusual circumstances.” TRW Inc., 534 U. S. at 29. The Government’s interpretation also conflicts with section 546’s statutory history. See Snyder v. United States, 603 U. S. 1, 12 (2024) (relying on “statutory history [to] reinforce [its] 11 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 1330 Page 12 of 26 PageID# textual analysis”); United States v. Hansen, 599 U. S. 762, 775 (2023) (“Statutory history is an important part of. context.”); Scalia & Garner, supra, at 440 (defining “statutory history” as the “enacted lineage of a statute, including prior laws, amendments, codifications, and repeals”). From 1986 to 2006, section 546 was identical to its current form. 12 See Criminal Law and Procedure Technical Amendments Act of 1986, Pub. L. No. 99-646, § 69, 100 Stat. 3592, 3616-17 (1986). But in 2006, Congress amended the statute to abolish “the 120-day limit and the district court’s backstopping role” altogether. Giraud II, 2025 WL 2416737, at *11; see USA PATRIOT Improvement and Reauthorization Act of 2005, Pub. L. No. 109-177, Title V, § 502, 120 Stat. 192, 246 (2006) [hereinafter Reauthorization Act]. This change, which was “inserted quietly into the conference report on the [Reauthorization] Act, without debate,” made it possible for “United States Attorneys appointed on an interim basis to serve indefinitely without Senate confirmation.” H. R. Rep. No. 110-58, at 5 (2007). “The switch to an unlimited appointment was short lived,” however. Giraud II, 2025 WL 2416737, at *11. Just over a year later, “Congress reverted to the pre-[Reauthorization] Act language,” reinstating the 120-day limit and the district court’s role in the interim appointment process. Id.; see Preserving United States Attorney Independence Act of 2007, Pub. L. No. 110- 12 Three days after Congress enacted the 1986 law, an Office of Legal Counsel (“OLC”) memorandum authored by then-Deputy Assistant Attorney General Samuel Alito concluded the statute does not allow “the Attorney General [to] make another appointment pursuant to [subsection (a)] after the expiration of the 120-day period.” Memorandum from Samuel A. Alito, Jr., Deputy Assistant Att’y Gen., Off. of Legal Couns., to William P. Tyson, Dir., Exec. Off. for U. S. Att’ys 3 (Nov. 13, 1986), available at “The statutory plan,” Alito reasoned, “discloses a Congressional purpose that after the expiration of the 120-day period further interim appointments are to be made by the court rather than by the Attorney General.” Id. Though not binding, OLC’s “contemporaneous” interpretation of section 546 further supports Ms. James’s position. Loper Bright Enters. v. Raimondo, 603 U. S. 369, 386, 388 (2024). 12 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 13 of 26 PageID# 1331 34, § 2, 121 Stat. 224 (2007) [hereinafter 2007 Act]. “When Congress amends legislation, courts must presume it intends [the change] to have real and substantial effect.” Ross v. Blake, 578 U. S. 632, 641-42 (2016) (internal quotation marks omitted). Yet if the Government’s reading were correct, the 2007 Act would have had virtually no effect, as it would still allow the Executive to evade the Senate confirmation process indefinitely by stacking successive 120-day appointments. Undeterred, the Government insists that “in reenacting the pre-2006 text, Congress presumptively ratified the Executive’s longstanding use of successive 120-day appointments under [the 1986-2006] version of the statute.” ECF No. 43 at 14. True, “a systematic, unbroken, executive practice, long pursued to the knowledge of the Congress and never before questioned, can raise a presumption that the [action] had been [taken] in pursuance of its consent.” Medellín v. Texas, 552 U. S. 491, 531 (2008) (alterations in original) (internal quotation marks omitted); see also NLRB. v. Noel Canning, 573 U. S. 513, 525 (2014) (“[T]he longstanding practice of the government can inform our determination of what the law is.” (internal citation and quotation marks omitted)). But the evidence on which the Government relies a handful of successive 120-day appointments across the Clinton and Bush administrations “longstanding” Executive practice. Cf. Am. Ins. Ass’n v. Garamendi, 539 U. S. 396, 415 (2003) (“Given the fact that the practice goes back over 200 years, and has received congressional acquiescence throughout its history, the conclusion that the President’s control of foreign relations includes the settlement of claims is indisputable.” (internal quotation marks omitted)). This is hardly establishes a 13 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 14 of 26 PageID# 1332 especially true when considering the Attorney General had no authority to appoint interim U. S. Attorneys at all before 1986. 13 See H. R. Rep. No. 110-58, at 4. Finally, “[f]or those who find it relevant, the legislative history confirms” Congress sought to eliminate the Executive Branch’s ability to circumvent the Senate’s advice-and-consent role through repeat or indefinite interim appointments. Honeycutt v. United States, 581 U. S. 443, 453 (2017). For example, in describing the pre-2006 framework, Senator Leahy explained Congress had “carefully circumscribed [the Attorney General’s authority to appoint an interim U. S. Attorney] by limiting it to 120 days, after which the district court would make any further interim appointment needed.” 153 Cong. Rec. S1994 (2007) (statement of Sen. Patrick Leahy). The 2007 Act, he stated, would “reinstate th[o]se vital limits on the Attorney General’s authority and bring back incentives for [an] administration to fill vacancies with Senate-confirmable nominees.” Id. Notably, Senator Leahy also rejected the notion that the Attorney General could “use the 120-day appointment authority more than once,” stating that the statute “is not designed or intended to be used repeatedly for the same vacancy.” Id. at S3299. Senator Feinstein, the 2007 Act’s primary sponsor, similarly stated that the legislation “would return the law to what it was before the change that was made in March of 2006.” Id. at S3298 (statement of Sen. Dianne Feinstein). She explained: It would still give the Attorney General the authority to appoint interim U. S. attorneys, but it would limit that authority to 120 days. If after that time, the President had not nominated a new U. S. attorney or the Senate had not confirmed a nominee, then the district courts would appoint an interim U. S. attorney. 13 By contrast, the judiciary’s authority to make interim appointments dates back to the Civil War. See Act of March 3, 1863, ch. 93, § 2, 12 Stat. 768 (1863). 14 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 15 of 26 PageID# 1333 Id. (emphasis added). Several other Senators echoed this understanding, 14 as did Members of the 15 House of Representatives. And the accompanying House Report explicitly identified “Bypassing the Requirement of Senatorial Advice and Consent” as a primary concern motivating the 2007 Act. H. R. Rep. No. 110-58, at 6. * * * In sum, the text, structure, and history of section 546 point to one conclusion: the Attorney General’s authority to appoint an interim U. S. Attorney lasts for a total of 120 days from the date she first invokes section 546 after the departure of a Senate-confirmed U. S. Attorney. If the position remains vacant at the end of the 120-day period, the exclusive authority to make further 14 153 Cong. Rec. S3240 (2007) (statement of Sen. Harry Reid) (remarking that the 2007 Act would “restore the pre-[Reauthorization] Act procedure,” which “allowed the chief Federal judge in the Federal district court to appoint a temporary replacement while the permanent nominee undergoes Senate confirmation”); id. at S3245 (statement of Sen. Arlen Specter) (“I think there is no doubt we ought to . go back to the old system where the Attorney General could appoint for 120 days, on an interim basis, and then after that period of time the replacement U. S. attorney would be appointed by the district court.”); id. at S3255 (statement of Sen. Ted Kennedy) (“The bill before us . reinstates the 120-day limit on service by interim U. S. attorneys appointed by the Attorney General. This change will force the administration to send nominees to the Senate to fill vacant slots, or have them filled by a court instead.”); id. at S3304 (statement of Sen. Carl Levin) (“The legislation before us today is simple: it would repeal [the] changes [in the Reauthorization Act] . and would require an interim appointment made by the Attorney General to expire after 120 days or when a successor is nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate, whichever comes first. If at the end of the 120-day period no successor has been confirmed, the relevant district court would be authorized to appoint an interim U. S. attorney to serve until the vacancy is filled.”). 15 153 Cong. Rec. H5553 (2007) (statement of Rep. John Conyers) (“[W]hat this measure does is restore the checks and balances that have historically provided a critical safeguard against politicization of the Department of Justice and the United States attorneys, limiting the Attorney General’s interim appointments to 120 days only, then allowing the district court for that district to appoint a U. S. attorney until the vacancy is filled[.]”); id. at H5554 (statement of Rep. Ric Keller) (“S. 214 returns the authority of the judiciary to appoint interim U. S. attorneys if a permanent replacement is not confirmed within 120 days.”); id. at H5555 (statement of Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee) (“This much needed and timely legislation . restore[s] the 120-day limit on the term of a United States Attorney appointed on an interim basis by the Attorney General.”). 15 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 16 of 26 PageID# 1334 interim appointments under the statute shifts to the district court, where it remains until the President’s nominee is confirmed by the Senate. Ms. Halligan was not appointed in a manner consistent with this framework. The 120-day clock began running with Mr. Siebert’s appointment on January 21, 2025. When that clock expired on May 21, 2025, so too did the Attorney General’s appointment authority. Consequently, I conclude that the Attorney General’s attempt to install Ms. Halligan as Interim U. S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia was invalid and that Ms. Halligan has been unlawfully serving in that role since September 22, 2025. B. Ms. Halligan’s appointment also violated the Appointments Clause. As discussed, the Appointments Clause allows Congress to “by Law vest” the appointment of inferior officers “in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments.” U. S. Const., art. II, § 2, cl. 2. Through section 546, Congress devised a statutory scheme that vests the appointment of interim U. S. Attorneys first in “the Head of [a] Department,” and then in “the Courts of Law.” Id. Because Ms. Halligan was appointed in violation of that scheme, her appointment was not authorized “by Law” and thus also violates the Appointments Clause. See United States v. Perkins, 116 U. S. 483, 485 (1886) (“The head of a department has no constitutional prerogative of appointment to offices independently of the legislation of congress, and by such legislation he must be governed, not only in making appointments, but in all that is incident thereto.”). Resisting this conclusion, the Government briefly asserts that “not every action ‘in excess of. statutory authority is ipso facto in violation of the Constitution.”” ECF No. 43 at 25 (quoting Dalton v. Specter, 511 U. S. 462, 472 (1994)). That is true but beside the point. “[A]n officer can[not] lawfully exercise the statutory power of [her] office at all” unless she has been “properly 16 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 1335 Page 17 of 26 PageID# appointed” under Article II. Collins v. Yellen, 594 U. S. 220, 266 (2021) (Thomas, J., concurring) (emphasis added). And here Ms. Halligan has not been appointed (1) by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate or (2) through a process Congress has authorized “by statute.” Kennedy, 606 U. S. at 804 (Thomas, J., dissenting) (“At the time of the framing, ‘by Law’ of course 999 meant ‘by statute.” (quoting Lucia, 585 U. S. at 254 (Thomas, J., concurring))). So an Appointments Clause violation has occurred. The next question is what to do about that violation. C. Dismissal of the indictment is appropriate. The Appointments Clause “is more than a matter of etiquette or protocol; it is among the significant structural safeguards of the constitutional scheme.” Edmond, 520 U. S. at 659 (internal quotation marks omitted). The Clause not only serves as “a bulwark against one branch aggrandizing its power at the expense of another,” Ryder v. United States, 515 U. S. 177, 182 (1995), but also “preserves another aspect of the Constitution’s structural integrity by preventing the diffusion of the appointment power,” Freytag v. Comm’r, 501 U. S. 868, 878 (1991). “Given its importance within our Constitution’s structure,” Cody v. Kijakazi, 48 F. 4th 956, 960 (9th Cir. 2022), “remedies with bite’ should be applied to appointments that run afoul of the Clause’s restrictions,” Brooks v. Kijakazi, 60 F. 4th 735, 740 (4th Cir. 2023) (quoting Cody, 48 F. 4th at 960). Here, Ms. James contends Ms. Halligan’s unlawful appointment renders all her purported official actions void ab initio. ECF No. 22 at 20. Ms. James therefore argues the case must be dismissed because Ms. Halligan was not lawfully exercising executive power when she appeared before the grand jury alone and obtained her indictment. See id. I agree. 999 “When an appointment violates the Appointments Clause from the jump, the actor has ‘exercise[d] power that [she] did not lawfully possess.” United States v. Giraud, No. 1: 24-CR- 00768, 2025 WL 2196794, at *8 (D. N. J. Aug. 1, 2025) (Giraud I) (alterations in original) (quoting 17 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 18 of 26 PageID# 1336 Collins, 594 U. S. at 258); see also Collins, 594 U. S. at 276 (Gorsuch, J., concurring in part) (explaining that when an officer is “unconstitutionally appointed,” “governmental action is taken and thus taken with no by someone erroneously claiming the mantle of executive power authority at all”); id. at 266 (Thomas, J., concurring) (“[A]n officer must be properly appointed before he can legally act as an officer.”). In such a case, “the proper remedy is invalidation of the ultra vires action[s]” taken by the actor. United States v. Trump, 740 F. Supp. 3d 1245, 1302 (S. D. Fla. 2024). “Invalidation ‘follows directly from the government actor’s lack of authority to take the challenged action in the first place. That is, winning the merits of the constitutional challenge is enough. Id. (quoting Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau v. All Am. Check Cashing, Inc., 33 F. 4th 218, 241 (5th Cir. 2022) (Jones, J., concurring)). In light of these principles, I conclude that all actions flowing from Ms. Halligan’s defective appointment, including securing and signing Ms. James’s indictment, constitute unlawful exercises of executive power and must be set aside. There is simply “no alternative course to cure the unconstitutional problem.” Trump, 740 F. Supp. 3d at 1303. The Government attempts to counter this result with several arguments, but none is persuasive. First, the Government argues that whatever her status as U. S. Attorney, Ms. Halligan still validly obtained and signed Ms. James’s indictment as an “attorney for the government.” ECF No. 43 at 21; see Fed. R. Crim. P. 1(b)(1) (defining an “[a]ttorney for the government” as “the Attorney General or an authorized assistant, a United States attorney or an authorized assistant,” or “any other attorney authorized by law to conduct proceedings under these rules as a prosecutor”); Fed. R. Crim. P. 6(d)(1) (“The following persons may be present while the grand jury is in session: attorneys for the government.”); Fed. R. Crim. P. 7(c)(1) (“The indictment 18 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 19 of 26 PageID# 1337 must be signed by an attorney for the government.”). In support of this argument, the Government relies on the Attorney General’s October 31 Order, which purported to retroactively appoint Ms. Halligan to the “additional position” of “Special Attorney,” effective September 22, 2025 17 days before Ms. James was indicted. Att’y Gen. Order No. 6485-2025. Although the Attorney General has “the power to appoint subordinate officers to assist [her] in the discharge of [her] duties,” United States v. Nixon, 418 U. S. 683, 694 (1974), the Government has identified no authority allowing the Attorney General to reach back in time and rewrite the terms of a past appointment. Nor can the variation between the September 22 and October 31 Orders be dismissed as a mere “paperwork error,” as suggested by the Government. ECF No. 43 at 28. The September 22 Order was unambiguous. The Attorney General stated she was appointing Ms. Halligan under 28 U. S. C. § 546 to “serve as the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia . for the period of one hundred and twenty days or until replaced in accordance with law, whichever occurs first.” Att’y Gen. Order No. 6402-2025. The October 31 Order then purported to appoint Ms. Halligan to an entirely different position (Special Attorney), under entirely different statutes (28 U. S. C. §§ 509, 510, and 515). Att’y Gen. Order No. 6485-2025. I reject the Attorney General’s attempt to retroactively confer Special Attorney status on Ms. Halligan. Regardless of what the Attorney General “intended,” ECF No. 43 at 23 (emphasis omitted), or “could have” done, id. at 28, the fact remains that Ms. Halligan was not an “attorney authorized by law” to conduct grand jury proceedings when she secured Ms. James’s indictment, 16 Fed. R. Crim. P. 1(b)(1)(D), 6(d)(1). 16 The Government attempts to frame the effect of Ms. Halligan’s invalid appointment as nothing more than a violation of Rule 7’s signature requirement. See ECF No. 43 at 23-24. The Footnote Continued . 19 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 1338 Page 20 of 26 PageID# Second, the Government contends that even if Ms. Halligan lacked the authority to obtain and sign indictments when she appeared before the grand jury, her actions should be entitled to “de facto validity.” ECF No. 43 at 24-25 (quoting Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U. S. 1, 142 (1976)). When applicable, the de facto officer doctrine “confers validity upon acts performed by a person acting under the color of official title even though it is later discovered that the legality of that person’s appointment or election to office is deficient.” Ryder, 515 U. S. at 180. “In other words, the doctrine operates so that a defect in an official’s appointment is not an adequate ground to challenge his earlier decisions.” Sidak v. U. S. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 678 F. Supp. 3d 1, 18 (D. D. C. 2023), appeal filed, No. 23-5149 (D. C. Cir. June 30, 2023). But the de facto officer doctrine “applies only to some non-constitutional appointments challenges.” Id. (emphasis in original); see, e. g., Ball v. United States, 140 U. S. 118, 128-29 (1891) (applying doctrine where an out-of-district judge assigned to replace a resident judge who had fallen ill continued to hold court after the resident judge’s death); McDowell v. United States, 159 U. S. 596, 601-02 (1895) (holding that a properly appointed judge assigned to another district was a “judge de facto” and that “his actions as such, so far as they affect[ed] third persons, [were] not open to question,” notwithstanding any question as to the validity of his designation). It has no application “when Appointments Clause challenges are involved.” Rop v. Fed. Housing Fin. Government is correct that courts have treated “the improper signing of an indictment,” Wheatley v. United States, 159 F. 2d 599, 601 (4th Cir. 1946), as a “technical deficienc[y]” that does not always require dismissal, United States v. Irorere, 228 F. 3d 816, 830-31 (7th Cir. 2000); see also 1 Wright & Miller’s Federal Practice & Procedure § 124 (5th ed. 2025) (observing that “courts have not rigorously enforced” Rule 7’s signature requirement). The problem here, though, is not just Ms. Halligan’s signature on the indictment she presented the indictment to the grand jury alone, without being a “proper representative of the Government.” United States v. Garcia- Andrade, No. 13-CR-993-IEG, 2013 WL 4027859, at *9 (S. D. Cal. Aug. 6, 2013). 20 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 1339 Page 21 of 26 PageID# Agency, 50 F. 4th 562, 587 (6th Cir. 2022) (Thapar, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part); SW Gen., Inc. v. NLRB, 796 F. 3d 67, 81 (D. C. Cir. 2015) (“In its most recent cases, . the Supreme Court has limited the doctrine, declining to apply it when reviewing Appointments Clause challenges[.]”); Sidak, 678 F. Supp. 3d at 17-19. In Ryder, a unanimous Supreme Court declined to apply the de facto officer doctrine to a claim that two judges on a panel of the Coast Guard Court of Military Review had been appointed in violation of the Appointments Clause. 515 U. S. at 179. The Court held that “one who makes a timely challenge to the constitutional validity of the appointment of an officer . is entitled to a decision on the merits of the question and whatever relief may be appropriate if a violation indeed occurred.”17 Id. at 182-83. “Any other rule,” it explained, “would create a disincentive to raise Appointments Clause challenges with respect to questionable . appointments.” Id. at 183. “[T]he Court then buried past precedents applying the doctrine,” including Buckley. Rop, 50 F. 4th at 587 (Thapar, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part). It declared, “To the extent [those] cases may be thought to have implicitly applied a form of the de facto officer doctrine, we are not inclined to extend them beyond their facts.” Ryder, 515 U. S. at 184. “After Ryder, the Supreme Court in Lucia ‘doubled down’ on its holding that ‘the de facto officer doctrine has no place when Appointments Clause challenges are involved,” Sidak, 678 F. Supp. 3d at 18 (quoting Rop, 50 F. 4th at 587 (Thapar, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part)), 17 Although Ryder concerned the appointment of adjudicators, “[t]here is no reason to limit the permissive approach to Appointments Clause claims and remedies where a defendant challenges the appointment of the party bringing criminal charges against him, as opposed to the party adjudicating the case.” Giraud I, 2025 WL 2196794, at *7. “The same ‘structural’ interests are at stake, because the allegation is that one branch has attempted to ‘aggrandiz[e] its power at the expense of another branch’ and thereby ‘diffus[e] the appointment power. Id. (quoting Freytag, 501 U. S. at 878). 21 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 22 of 26 PageID# 1340 reaffirming that a party who raises a timely Appointments Clause claim is “entitled to relief,” Lucia, 585 U. S. at 251; see also id. at 251 n. 5 (explaining that “Appointments Clause remedies are designed” both “to advance [the Clause’s structural] purposes directly” and “to create incentive[s] to raise Appointments Clause challenges” in the first place (internal quotation marks omitted)). Given the Court’s holdings in Ryder and Lucia, the de facto officer doctrine does not bar the relief sought by Ms. James. Third, the Government submits that the grand jury’s “independent decision” to indict Ms. James renders any error in her indictment harmless. ECF No. 43 at 27-29. The “customary harmless-error inquiry” is normally “applicable where . a court is asked to dismiss an indictment prior to the conclusion of the trial.” Bank of Nova Scotia v. United States, 487 U. S. 250, 256 (1988). Harmless-error analysis does not apply, however, when “the structural protections of the grand jury have been so compromised as to render the proceedings fundamentally unfair.” Id. at 257. This case presents the unique, if not unprecedented, situation where an unconstitutionally appointed prosecutor, exercising “power [she] did not lawfully possess,” Collins, 594 U. S. at 258, acted alone in conducting a grand jury proceeding and securing an indictment. In light of the near- complete control that prosecutors wield over the grand-jury process, 18 such an error necessarily “affect[s] the entire framework within which the proceeding occurs,” Greer v. United States, 593 U. S. 503, 513-14 (2021), and thus “def[ies] analysis by ‘harmless-error’ standards,” Arizona v. 18 Although the grand jury is understood to be “a constitutional fixture in its own right,” United States v. Williams, 504 U. S. 36, 47 (1992) (internal quotation marks omitted), it is “easy to overstate the grand jury’s independence from the prosecutor,” 1 Wright & Miller’s Federal Practice & Procedure § 102 (5th ed. 2025). Indeed, it is the prosecutor “who decides which investigations to pursue, what documents to subpoena, which witnesses to call, and what charges to recommend for indictment.” 1 Wright & Miller, supra, § 102. And it is the prosecutor who examines the witnesses, summarizes the evidence, and advises the grand jury on the law. 22 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 23 of 26 PageID# 1341 Fulminante, 499 U. S. 279, 309 (1991); cf. Young v. United States ex rel. Vuitton et Fils S. A., 481 U. S. 787, 812-14 (1987) (plurality opinion) (holding that “harmless-error analysis is inappropriate in reviewing the appointment of an interested prosecutor” in part because “[s]uch an appointment calls into question, and therefore requires scrutiny of, the conduct of an entire prosecution, rather than simply a discrete prosecutorial decision”). As a final fallback position, the Government argues that even if Ms. James’s indictment is flawed, dismissal is inappropriate because the Attorney General has since ratified Ms. Halligan’s actions before the grand jury and her signature on the indictment. ECF No. 43 at 29-30; see Att’y Gen. Order Nos. 6485-2025, 6495-2025. Even assuming the agency-law doctrine of ratification can be used to cure a defective indictment (the Government cites no authority holding as much), the Attorney General’s attempt at ratification here fails. “Ratification is the affirmance by a person of a prior act which did not bind him but which was done or professedly done on his account.” Restatement (Second) of Agency § 82 (1958). In effect, the doctrine “reaches back and makes it so that a formerly unauthorized act was authorized from the get-go.” Wille v. Lutnick, _ F. 4th, 2025 WL 3039191, at *8 (4th Cir. Oct. 31, 2025). But for ratification to be effective, “the principal must have [had] the authority to authorize the action . when the action [was] initially performed by the agent.” Id. The Attorney General lacked that authority here. I have already concluded that Ms. Halligan’s original appointment was invalid and that the Attorney General’s attempt to retroactively bestow Special Attorney status on her was ineffective. As a result, the Attorney General “could not have authorized” Ms. Halligan, who was not an attorney for the Government at the time, to present Ms. James’s indictment to the grand jury on October 9. Restatement (Second) of Agency, supra, § 84(2) (stating that if “the purported or 23 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 24 of 26 PageID# 1342 intended principal could not have authorized” the challenged “act” when it was “done,” “he cannot ratify” it). The implications of a contrary conclusion are extraordinary. It would mean the Government could send any private citizen off the street into the grand jury attorney or not room to secure an indictment so long as the Attorney General gives her approval after the fact. That cannot be the law. D. Dismissal will be without prejudice. Having found that Ms. Halligan’s appointment violated 28 U. S. C. § 546 and the Appointments Clause and that dismissal of Ms. James’s indictment is warranted, the remaining issue is whether dismissal should be with or without prejudice. Ms. James’s motion does not specifically request dismissal with prejudice. The Government argues she has thus forfeited the request. ECF No. 43 at 30. In her reply brief, however, Ms. James urges me to exercise my supervisory powers and dismiss her indictment with prejudice. ECF No. 56 at 25. A with- prejudice dismissal is necessary, she argues, to “promote the interests protected by the Appointments Clause” and to “deter the government from deploying unlawful appointments to effectuate retaliation against perceived political opponents.” Id. at 24; see United States v. Hasting, 461 U. S. 499, 505 (1983) (recognizing that a court may use its “supervisory powers” to “implement a remedy for violation of recognized rights” and “as a remedy designed to deter illegal conduct”). Ultimately, I believe the Supreme Court’s Appointments Clause jurisprudence provides the answer to the with-or-without-prejudice question. In both Ryder and Lucia, the Court essentially unwound the actions taken by the unconstitutionally appointed officer and restored the affected party to the position the party occupied before being subjected to those invalid acts. See Ryder, 515 U. S. at 188 (remanding for a new “hearing before a properly appointed panel”); Lucia, 585 24 Case 2: 25-cr-00122-JKW-DEM Document 140 Filed 11/24/25 Page 25 of 26 PageID# 1343 U. S. at 251 (“[T]he ‘appropriate’ remedy for an adjudication tainted with an appointments violation is a new ‘hearing before a properly appointed’ official.” (quoting Ryder, 515 U. S. at 183, 188)); see also Nguyen v. United States, 539 U. S. 69, 83 (2003) (vacating decisions made by an appeals panel that included a judge who was ineligible to sit by designation on an Article III court and remanding “for fresh consideration of petitioners’ appeals by a properly constituted panel”). I will do the same here. I will invalidate the ultra vires acts performed by Ms. Halligan and dismiss the indictment without prejudice, returning Ms. James to the status she occupied before being indicted. See Trump, 740 F. Supp. 3d at 1303, 1309. III. CONCLUSION For the reasons set forth above, it is hereby ORDERED AND ADJUDGED as follows: 1. 2. 3. 4. The appointment of Ms. Halligan as Interim U. S. Attorney violated 28 U. S. C. § 546 and the Appointments Clause of the U. S. Constitution. All actions flowing from Ms. Halligan’s defective appointment, including securing and signing Ms. James’s indictment, were unlawful exercises of executive power and are hereby set aside. The Attorney General’s attempts to ratify Ms. Halligan’s actions were ineffective and are hereby set aside. Ms. James’s motion to dismiss the indictment (ECF No. 22) is granted in accordance with this order. 5. The indictment is dismissed without prejudice. 6. Ms. James’s request for an injunction barring Ms. Halligan from participating in the prosecution of this case is denied as moot.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/11/24/us/letitia-james-ruling.html

Read the Ruling Dismissing the Charges Against Letitia James

Be First to Comment